Echoes between the shelf: how Mrs Affleck's Affliction gave PR a soul

Published: 4 November 2025 | Updated: 4 November 2025 | By: Newcastle University | 2 min read

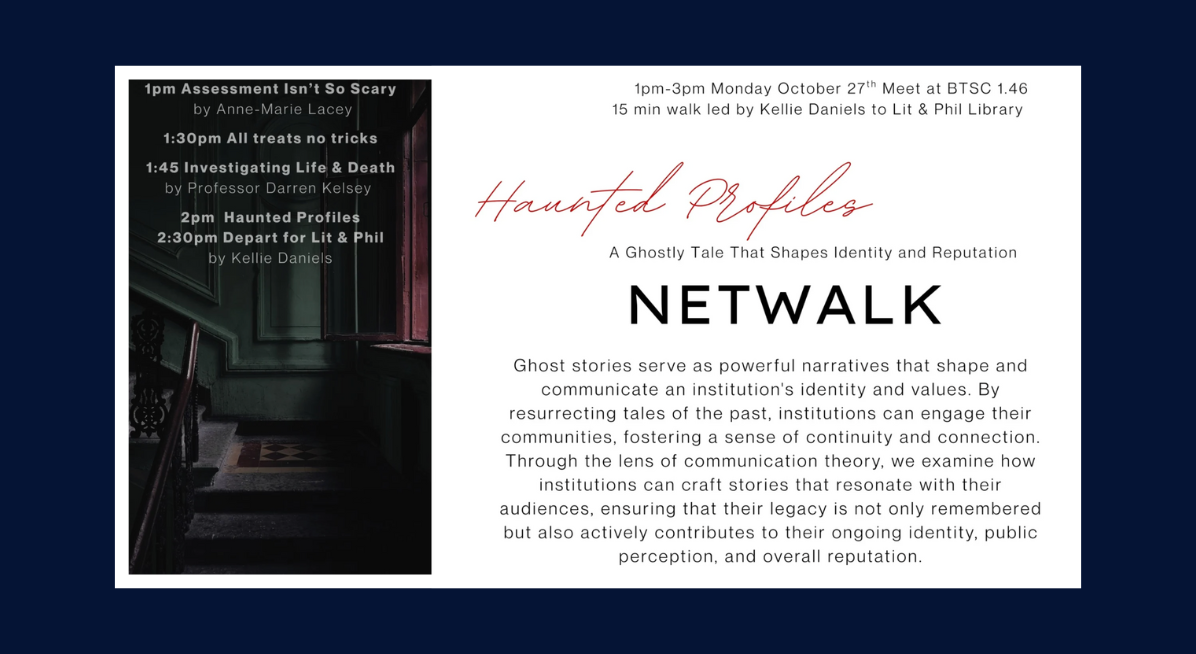

On 27 October, we attended a fascinating on-campus networking session led by our lecturer Kellie, who had previously taken us to the Laing Art Gallery to explore how art communicates meaning and ideology through visual elements.

This time, the focus was on the Lit & Phil Library, one of Newcastle’s oldest cultural spaces, and how institutions like it use storytelling and media to connect with the public.

As we gathered for the session, the room had a relaxed, inviting atmosphere with soft chatter, trays of treats being passed around, and the hum of curiosity about what we were about to watch.

Kellie introduced us to the story of "Mrs Affleck’s Affliction", a 15-minute short film created as part of Lit & Phil’s 200th anniversary project.

The library had invited the public to submit stories about its people, and one entry about Mrs Affleck, a cleaner who worked there, was selected and turned into this film.

We watched the film together on the big screen. It felt intimate yet powerful, a quiet story that somehow said a lot about whose voices are remembered and whose are not.

After the screening, Kellie opened up the floor and asked us to identify the signifiers we noticed, the objects, visuals, and details that conveyed deeper meanings about class, gender, and power.

First: the power-dynamics. Mrs Affleck is positioned not as a hero in the traditional sense but as someone whose labour is invisible, whose voice is rarely heard.

By choosing her as the focus, the library automatically inverts the usual hierarchical story of building, donor, institution, and benefactor. The cleaner becomes the narrator: this gesture signals a subtle critique of whose labour counts in a cultural institution and whose voice is amplified.

Secondly, the institutional self-representation and PR dimension. The Lit & Phil is celebrating its bicentenary and chooses to commission this film, invite stories from the public, and frame its own history through one of its most modest staff.

That is a brilliant public relations (PR) move: rather than simply boast '200 years of books and scholars', the institution says: 'we value everyone, we listen to voices from the margins, we humble ourselves and tell a different story'. In doing so the Library reframes itself as inclusive, socially aware, progressive.

The discussion further revealed how every choice in the film communicated something. The dim lighting and repetitive sound of sweeping reflected the quiet invisibility of Mrs Affleck’s work.

The contrast between the grandeur of the library’s architecture and her solitary figure underscored how institutions often depend on unseen labour.

Even the use of voice-over gave her a kind of agency, a voice she might never have been given in real life. These were not just artistic decisions; they were ideological ones, subtly challenging traditional power hierarchies and gender roles.

From a public relations perspective, I found this initiative absolutely brilliant. Instead of celebrating 200 years through a self-congratulatory timeline, the Lit & Phil chose to tell its story through someone most people would overlook.

By inviting the public to contribute stories and turning one of them into a film, the institution shifted from one-way communication to symmetrical communication, where the audience becomes part of the storytelling. It built emotional connection, authenticity, and community trust, which are core principles of effective PR.

Personally, I found the session incredibly insightful. It showed me how PR does not always have to be loud or flashy; sometimes the most powerful communication comes from humility and inclusion.

The Lit & Phil used art to reshape its image, aligning itself with values of empathy, equality, and shared heritage.

What I took away most was how a well-crafted narrative, even about a cleaner, can humanise an institution, strengthen its public identity, and invite people to see themselves within its story.

In the end, it was not just a film screening; it was a reminder that storytelling, when done thoughtfully, can be both art and strategy.